ASIA

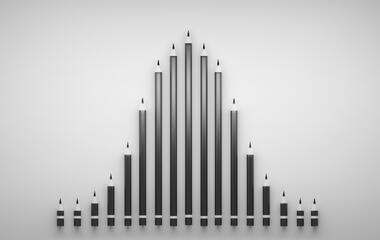

Why the Bell Curve system for giving grades needs reform

Grading on a curve, particularly the Bell Curve, remains a highly controversial topic in education, from schools to higher education institutions.Although the Bell Curve grading system has received much criticism from teachers, students and employers, it continues to be practised by certain universities, including a small number of Asian institutions.

This grading system is largely used to determine students’ final grades in a module or programme as well as their overall Grade Point Average (GPA). There are no statistics about the percentage of universities and colleges that still employ the Bell Curve, but based on multiple sources we are certain that they are in the minority. And in institutions where grading to a curve is evident, this practice may not be a university-wide policy.

One of the most notable characteristics of the Bell Curve grading system is how specific grades are moulded into a curve with a bell shape. In this curve, only a small percentage of students are deemed able to achieve A’s whereas other students are assigned lower grades, mostly B’s and-or C’s, regardless of how well they perform in class and in assignments and exams.

Justifications for the Bell Curve

The Bell Curve is seen as producing a normal distribution of grades within schools and universities by those who adopt it. Justifications for the Bell Curve often highlight its main purpose of preventing grade inflation from happening within an institution.

Specifically, the Bell Curve is used to ensure that the high value attributed to an ‘A’ is maintained because only a small percentage of students can be awarded it.

It is alleged that a high ‘A’ grade will be devalued if many A’s are given. According to this perspective, when a high number of students achieves an ‘A’ from their assessments or exams, their educational achievements may be valued less as it appears easy to attain a high grade.

This perception of ‘devalued’ A’s might then put a university’s global and national credibility and reputation at risk, meaning, for instance, that they could lose potential students or investors as a result.

At the same time, in situations where there are many ‘Fails’ among any cohort of students or in any programmes, students’ grades will be brought up to ensure that a Bell Curve is obtained. In this way the university can show that its students are not doing so poorly overall. Proponents of the Bell Curve often cite this as bringing benefits to students, particularly those who are at the lower end of the educational spectrum.

Those advocating for the Bell Curve consider it to be fair and to reflect the actual capabilities of students in education and in society. However, it should be noted that many schools and universities have opted out of this Bell Curve grading system or have never adopted it in the first place.

Listening to students

Here is what some students say about it.

One said: “It’s unfair. I worked so hard throughout the semester, and all I got was a B. If this final grade was given by my lecturer, I’d feel betrayed because all my individual assessment tasks actually added up to a much higher grade.

“But if this was the grade determined randomly by the Bell Curve policy at my university, then I don’t see any purpose and meaning for university education. What’s the point of working hard and going the extra mile to learn and improve your knowledge and then having your fate being arbitrarily decided by that curve?”

Another said: “I’ve lost my motivation to study. I’m not the only one. Many of us have. Why should I work day and night for all my classes when at the end of the day what matters to the university is how our grade percentage fits a predetermined curve?

“Nobody explains anything to us about all of this. Everything is so vague about assessment because this lack of transparency allows the university to manipulate our grades under the so-called Bell Curve policy. I’ve also heard that lecturers are under pressure to give us grades that would fit within a target curve.”

Yet another stated: “I’ve learnt that the Bell Curve is not implemented at many universities around the world. If anything, many universities and schools have moved away from this practice, following lots of criticism.

“It feels terrible to know that our university continues to use it on us. It’s so sad that our entire university education has been subjected to this unfair practice. I used to accept it because I thought it was a natural thing that all universities do. I never questioned it. What’s the point now; I’m almost at the end of this painful journey.”

And another commented: “My friends go to different local universities and their universities don’t follow the Bell Curve grading. I don’t know any student who has ever queried their grades at my university because we’ve been made to accept whatever is given to us. You know that you’re already lost before you even try.

“My GPA is pretty low because of this whole Bell Curve thing. Your efforts don’t match the grades you get, because only a small few will get the top grades. It’s easier to get a C than to fail. We all know it.”

Another comment went as follows: “It’s an unfair system. There is nothing educational about it. It’s there to make universities such as mine not have to think much because they already determine the percentage of A’s, B’s, C’s even before students’ grades or marks come in. Who benefits from it? Only their institutions, not students, not employers.”

The above accounts are just some of the many comments from students shared with us from students at an Asian university whose grades have been determined by their institution’s Bell Curve grading policy.

We obtained their accounts as part of a project we conducted on assessment in higher education, following the critical examination of key issues and topics we were introduced to in the module “Education and Society in a Globalised World” offered at Universiti Brunei Darussalam.

Concerns and criticisms

Over the years, various stakeholders in education have pointed out the many flaws and problems regarding the implementation of the Bell Curve in assessment and grading. Criticisms of the Bell Curve are abundant in academic literature. Critics see this policy and practice as perpetuating and re-enforcing an unhealthy competitive environment within educational settings.

Likewise, concerns about grade deflation have been expressed by academics such as Adam Grant, a professor at the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania in the United States.

Instead of encouraging motivation and innovation, grading on the Bell Curve has caused harm to both teachers and students in many ways. Rather than giving students the grades that reflect their actual performance, the Bell Curve mandate forces professors to judge students’ performances against those of others.

The Bell Curve also demands that professors only give a limited number of A’s in a module and a course, regardless of how well students do. Hence, many A-deserving students will be given a B or even a lower grade for the bell shape to be achieved.

Sean Lim Wei Xin, a Singaporean university student, has described the Bell Curve system as creating a “dog-eat-dog learning culture”.

Based on his experience of attending two different institutions, one in Singapore that employed the Bell Curve grading system and one in Sweden that did not, he concluded that students who were graded according to their performance were more helpful and willing to help each other to flourish rather than only caring about themselves.

Students who were graded on the curve, however, were often pitted against each other for higher grades in class. Sean also felt that the Bell Curve system would hamper any education reforms and therefore believed it should be discarded.

Sean’s advocacy is indeed echoed in much academic literature from the past several decades; and his experience with the Bell Curve grading system is shared by many students, including the students mentioned above.

Some revealed that, because of the tendency to internalise the ‘bell-curve mentality’, students are reluctant to help one another as they see each other as competitors rather than co-learners or collaborators. This distasteful experience of learning can affect the emotional state of students, making them feel pressured to become the ‘best of the best’ as they fight to be ranked within those students who can obtain an A.

Even in situations where students find grading on the Bell Curve generally fair, they have expressed concerns about its negative impacts on learning. Such negative impacts can also lead to a high level of stress and related mental health problems among students and such harmful effects must not be underestimated.

Bad for students and professors

The educational experience caused by the Bell Curve system goes against the true purpose of education. Many educators would agree that university education should be conducted in an environment that promotes a joy for learning as well as hard work, teamwork and collaborative work alongside individual growth. University education should enable students to take pride in and share their achievements and determination.

Moreover, professors and students both suffer from having their performance judged along a curve. The dedication and innovation that professors may attempt to pass on to their students are not taken into consideration.

The curve also makes all teaching equal, meaning that professors who put little effort into inspiring students to learn are viewed the same as those who put their whole heart into their students’ education. Professors whose students are awarded high grades are suspected of being lenient instead of being recognised for their ability to bring students’ learning up to a higher standard.

The system can also demotivate students. In grade moderation practice, students’ grades are often downgraded by either their professors or by some authority in their university so a bell curve can be achieved. In this situation, the grades allocated to students may be a misleading account of how much the student has learned.

Students who work hard and strive for the best often feel demotivated by this unfair practice as they may well be those whose grades will be brought down, while some ‘lucky’ ones “whom everyone knows don’t deserve it” are given higher grades in the same process.

There is no guarantee that students will be considerate towards those with an ‘A’ grade and vice versa when they are concerned about fairness and the harm caused by the Bell Curve grading system.

It is time for institutions that use the Bell Curve to reform their grading system to ensure that students are judged on their merit and are able to achieve their potential without being arbitrarily limited.

Aida Murad and Haziqah Jefri are majoring in sociology and anthropology at Universiti Brunei Darussalam. Phan Le Ha is head of the International and Comparative Education Research Group and senior professor in the Sultan Hassanal Bolkiah Institute of Education, Universiti Brunei Darussalam (UBD). She also teaches in the faculty of arts and social sciences at UBD. Phan Le Ha maintains her affiliation with the University of Hawaii at Manoa. This article is part of a series, ‘Sociology Students Write Back and Forward’ that Phan Le Ha initiated with her students. The first article, which gives an overview, can be read here. The second part of this article will focus on alternatives to the Bell Curve system.